Dear Reader,

Three entries in three months tells me I am taking the wrong approach, and usually this kind of blockage means I am following a broken system, a Procrustean way of organizing my material that does not fit it well. Such is the case here. So far my mistakes include 1) trying to fit the material into a fixed number and sequence, 2) trying to present them as distilled down into principles, 3) presenting them as a teacher rather than as a student.

I am in no way prepared to teach this material, which I am still wrestling with myself, but I am prepared to share my explorations with you, and to discuss them with anyone who wants to comment.

Yours truly,

Rick

Exploring the human condition in daily bites. An experiment in how to address large, complex issues with a long series of small essays - and in how to make philosophically thorny topics more accessible without distorting them.

Monday, December 25, 2006

Sunday, December 24, 2006

Culturing Our Wants

Dear Reader,

Heraclitus wrote Anthrôpoisi ginesthai hokosa thelousi ouk ameinon, which Philip Wheelwright translates as It would not be better if things happened to men just as they wish. In other words, if things turned out exactly as we want them to turn out, we would be sorry.

In a simple-minded, caricatured way, this theme is played upon in stories about how genies freed from bottles or lamps always twist our wishes to make us sad, but what Heraclitus is saying is far more profound: if the wishes were not twisted at all, if things turned out exactly as we want them, without any tricks, we would be sad. What we want is not healthy for us. We understand ourselves, the cosmos, and our place in it so poorly that want the wrong things.

This is heresy to us, whether we recognize it as such or not, which is why our stories mock this profundity with our petty stories of malicious genies trying to cheat us out of what is rightly ours. We love our appetites; we adore them; we worship them. We long for fortune to bless us so we can indulge those wants, passionately sure that satisfying our cravings will bring us lasting happiness. Those "sophisticated" enough to give in to despair, who believe they are free of such illusions about their desires, in their ironic detachment do not find happiness either; they are dispassionate and flat personalities because all their passion is still tied up as faith in the things they used to want, and now that they have moved past those wants they have also left behind their zest for life. To the ego, whether naively clinging to its longings or half-dead from bitterly amused detachment from them, desire is the only fuel it has to stoke the fires of a passionate life. For Heraclitus to say that the things we want, our goals, our dreams, our aspirations, our hopes, all will lead us to misery, is a kick in the gut to tell us to stop "thinking" with our gut.

At this point in my entry, I have lost all the intellectuals, since they think this applies to everyone but themselves. Much of my life has been a case-study of the futility of overintellectualization, the discovery that the attempt to identify oneself strictly with the intellect instead of the emotions merely puts an intellectual rationalizing veneer over what then become more unconscious and barbaric emotions. The solution to Heraclitus's puzzling insight is not to try to escape from our wants nor to strive to create a personality that somehow replaces desire with some other kind of passionate furnace - such things are impossible for us. We are not Protean, angelic beings of pure reason who can will ourselves into different forms; we are animals evolved within the matrix of nature and given form, drive, and direction by the forces of nature within us.

We can only become what we already are, like seeds unfolding into flowers. If the things we want drive us, then to improve ourselves we must improve the things we want. We must culture our wants to want better things. To do that, we have to achieve a profoundly better understanding of the cosmos, ourselves, and our place in the cosmos, since only in an accurate understanding of such things have we any basis for knowing what we ought to want. And in the end, although we cannot escape our investment in wanting, since that is the foundation of human personality, we can at least learn not to strive for happiness (that transient fool's-gold that the wheel of fortune gives and then takes away) but for eudaimonea or eucosmia (the well-order inner cosmos of character that results from the process of culturing oneself and one's wants), which creates the ability to make the most of whatever life offers us.

Lit by such ancient Greek ideas, Heraclitus's statement takes on a radically different meaning than it would if read merely as pessimism, fatalism, or schadenfreude. Read deeply, his statement demands that we change. Like many of his statements, this one implies that to make a better world, we need to become better people.

Yours truly,

Rick

Heraclitus wrote Anthrôpoisi ginesthai hokosa thelousi ouk ameinon, which Philip Wheelwright translates as It would not be better if things happened to men just as they wish. In other words, if things turned out exactly as we want them to turn out, we would be sorry.

In a simple-minded, caricatured way, this theme is played upon in stories about how genies freed from bottles or lamps always twist our wishes to make us sad, but what Heraclitus is saying is far more profound: if the wishes were not twisted at all, if things turned out exactly as we want them, without any tricks, we would be sad. What we want is not healthy for us. We understand ourselves, the cosmos, and our place in it so poorly that want the wrong things.

This is heresy to us, whether we recognize it as such or not, which is why our stories mock this profundity with our petty stories of malicious genies trying to cheat us out of what is rightly ours. We love our appetites; we adore them; we worship them. We long for fortune to bless us so we can indulge those wants, passionately sure that satisfying our cravings will bring us lasting happiness. Those "sophisticated" enough to give in to despair, who believe they are free of such illusions about their desires, in their ironic detachment do not find happiness either; they are dispassionate and flat personalities because all their passion is still tied up as faith in the things they used to want, and now that they have moved past those wants they have also left behind their zest for life. To the ego, whether naively clinging to its longings or half-dead from bitterly amused detachment from them, desire is the only fuel it has to stoke the fires of a passionate life. For Heraclitus to say that the things we want, our goals, our dreams, our aspirations, our hopes, all will lead us to misery, is a kick in the gut to tell us to stop "thinking" with our gut.

At this point in my entry, I have lost all the intellectuals, since they think this applies to everyone but themselves. Much of my life has been a case-study of the futility of overintellectualization, the discovery that the attempt to identify oneself strictly with the intellect instead of the emotions merely puts an intellectual rationalizing veneer over what then become more unconscious and barbaric emotions. The solution to Heraclitus's puzzling insight is not to try to escape from our wants nor to strive to create a personality that somehow replaces desire with some other kind of passionate furnace - such things are impossible for us. We are not Protean, angelic beings of pure reason who can will ourselves into different forms; we are animals evolved within the matrix of nature and given form, drive, and direction by the forces of nature within us.

We can only become what we already are, like seeds unfolding into flowers. If the things we want drive us, then to improve ourselves we must improve the things we want. We must culture our wants to want better things. To do that, we have to achieve a profoundly better understanding of the cosmos, ourselves, and our place in the cosmos, since only in an accurate understanding of such things have we any basis for knowing what we ought to want. And in the end, although we cannot escape our investment in wanting, since that is the foundation of human personality, we can at least learn not to strive for happiness (that transient fool's-gold that the wheel of fortune gives and then takes away) but for eudaimonea or eucosmia (the well-order inner cosmos of character that results from the process of culturing oneself and one's wants), which creates the ability to make the most of whatever life offers us.

Lit by such ancient Greek ideas, Heraclitus's statement takes on a radically different meaning than it would if read merely as pessimism, fatalism, or schadenfreude. Read deeply, his statement demands that we change. Like many of his statements, this one implies that to make a better world, we need to become better people.

Yours truly,

Rick

Monday, October 23, 2006

Critique of My False Analogies

Dear Reader,

You are not in as much luck as I predicted. Not only the title of the previous post is confusing, but also the initial parts of my explanation. The second half of the essay, which explains why this principle is necessary to understanding the ancient Greek philosophers, is largely correct, but the preceding explanation of what those two cultures were is misleading. I conflated four different pairs of ideas and omitted a far more direct explanation necessary to understanding that first principle.

Rather than retract, revise, and republish the previous post, we will find it more useful to critique it instead. I am not interested in striving to create an illusion of perfection in my writing. If we are fortunate and disciplined enough, our ideas begin in obscurity but develop greater wisdom and suppleness over time. That is certainly my aim, and exposing my weaknesses is a better way to foster my own development than hiding them.

So what is wrong with the previous attempt to explain the ancient Greek transition from a Mythos culture to a Logos culture?

I tried to explain the dichotomy between the two kinds of cultures by analogizing to three other dichotomies: between the rationalist left-brain and the intuitivist right-brain, between the conscious and the unconscious parts of the mind, and between the Apollonian and the Dionysian. None of these analogies is quite right, and the poor fits confuse. In her comment on my essay, Linda Yaw noted some of the implications of these conflations and questioned whether she was understanding the idea correctly. Her comment helped me realize that although she was understanding what I wrote, what I wrote was not quite right. I will try to improve my explanation first negatively in this post, by explaining the kind of confusion I created, and then positively in the next post, by explaining the difference between the two kinds of culture directly with minimal recourse to analogies to other dichotomies.

The dichotomy between rationalism and intuitivism is not accurate because it is an effect, not a cause, of the difference between Logos and Mythos cultures, nor is it a parallel dichotomy. In a Mythos culture, the emphasis is on traditional wisdom, values, and other norms that have accumulated over long periods of time, rather than on the use of any particular mental faculty. In such a culture, rationalism and intuitivism will have whatever balance of emphasis they naturally acquired within that culture over time. In the case of Greek Mythos-culture, the balance was fairly even, with different aspects of the culture favoring different mental approaches. In a Logos culture, however, the emphasis is on rationalism above all else, leading to a radical imbalance that ultimately erodes all traditional wisdom, values, and other norms. It is not the rationalism per se that leads to this result, as rationalism was already present in the preceding Mythos culture, but rather how and why it is used, which I will explore in the next post.

The dichotomy between consciousness and unconsciousness is far more misleading and yet also paradoxically points to the true issue. All individuals and cultures operate consciously, but that consciousness grows from a far greater unconscious realm: all cultures, so this applies to both Logos and Mythos cultures. With respect to this dichotomy, the difference between them is one of attitude. A Mythos culture reveres and operates consciously within its traditional, inherited, natural, unconscious matrix, but a Logos culture despises and struggles to escape from that matrix. That quest for freedom from the unconscious is ultimately futile and does violence to the integrity of the culture itself, since consciousness is not possible without a healthy unconscious foundation, which I will explore in the next post.

The least revealing analogy was unfortunately the clearest, between the Apollonian and Dionysian. This dichotomy, popular and seemingly coherent though it is, is far more complex and means something quite different than authors or readers realize. It is usually taken to be a richer, more poetic, more mythologized version of the dichotomy between rationalism and intuitivism; that was how I meant it, and that usage was wrong for the reasons described above. The more serious error is that Apollonianism and Dionysianism, although intended to describe the differences between left-brained and right-brained mentalities, do nothing of the sort. Instead they describe a whole-brained mentality's wistful, romanticized fantasy of what those two modes might be like; the truth of the two half-wit, crack-brained mentalities is far darker and more dysfunctional than the Apollonian and Dionysian fantasies allow. All three mentalities, the whole-brained and both half-brained imbalances, exist in both Logos and Mythos cultures, but in different ratios. A Mythos culture will have whatever proportion of these three mentalities in its population that naturally developed there, but a Logos culture will tend to elevate left-brained mentalities to domination over the right-brained, with the whole-brained mentalities marginalized. None of this corresponds to a simple Apollonian-Dionysian dichotomy, even if that dichotomy had any validity outside the realm of poetry. Explaining Logos and Mythos culture using these terms was quite unhelpful.

Stripping these three false analogies back out of my explanation, we are still left with the original pair in the dichotomy underlying this first principle: Mythos culture and Logos culture. Aside from the confusion introduced by trying to explain them in terms of three supposedly analogous dichotomies, the most important problem is that in doing so I danced around the heart of the matter. Rather than draw further analogies to other dichotomies I will do better to explain Mythos and Logos cultures in terms of what they have in common; they are cultures first of all, so explaining them should begin with the nature and function of culture before contrasting their divergent expressions of it. I hope my next post will explain this crucial first principle underlying ancient Greek philosophy far more clearly.

Yours truly,

Rick

Postscript: And I hope I get my explanation of the second principle right the first time.

You are not in as much luck as I predicted. Not only the title of the previous post is confusing, but also the initial parts of my explanation. The second half of the essay, which explains why this principle is necessary to understanding the ancient Greek philosophers, is largely correct, but the preceding explanation of what those two cultures were is misleading. I conflated four different pairs of ideas and omitted a far more direct explanation necessary to understanding that first principle.

Rather than retract, revise, and republish the previous post, we will find it more useful to critique it instead. I am not interested in striving to create an illusion of perfection in my writing. If we are fortunate and disciplined enough, our ideas begin in obscurity but develop greater wisdom and suppleness over time. That is certainly my aim, and exposing my weaknesses is a better way to foster my own development than hiding them.

So what is wrong with the previous attempt to explain the ancient Greek transition from a Mythos culture to a Logos culture?

I tried to explain the dichotomy between the two kinds of cultures by analogizing to three other dichotomies: between the rationalist left-brain and the intuitivist right-brain, between the conscious and the unconscious parts of the mind, and between the Apollonian and the Dionysian. None of these analogies is quite right, and the poor fits confuse. In her comment on my essay, Linda Yaw noted some of the implications of these conflations and questioned whether she was understanding the idea correctly. Her comment helped me realize that although she was understanding what I wrote, what I wrote was not quite right. I will try to improve my explanation first negatively in this post, by explaining the kind of confusion I created, and then positively in the next post, by explaining the difference between the two kinds of culture directly with minimal recourse to analogies to other dichotomies.

The dichotomy between rationalism and intuitivism is not accurate because it is an effect, not a cause, of the difference between Logos and Mythos cultures, nor is it a parallel dichotomy. In a Mythos culture, the emphasis is on traditional wisdom, values, and other norms that have accumulated over long periods of time, rather than on the use of any particular mental faculty. In such a culture, rationalism and intuitivism will have whatever balance of emphasis they naturally acquired within that culture over time. In the case of Greek Mythos-culture, the balance was fairly even, with different aspects of the culture favoring different mental approaches. In a Logos culture, however, the emphasis is on rationalism above all else, leading to a radical imbalance that ultimately erodes all traditional wisdom, values, and other norms. It is not the rationalism per se that leads to this result, as rationalism was already present in the preceding Mythos culture, but rather how and why it is used, which I will explore in the next post.

The dichotomy between consciousness and unconsciousness is far more misleading and yet also paradoxically points to the true issue. All individuals and cultures operate consciously, but that consciousness grows from a far greater unconscious realm: all cultures, so this applies to both Logos and Mythos cultures. With respect to this dichotomy, the difference between them is one of attitude. A Mythos culture reveres and operates consciously within its traditional, inherited, natural, unconscious matrix, but a Logos culture despises and struggles to escape from that matrix. That quest for freedom from the unconscious is ultimately futile and does violence to the integrity of the culture itself, since consciousness is not possible without a healthy unconscious foundation, which I will explore in the next post.

The least revealing analogy was unfortunately the clearest, between the Apollonian and Dionysian. This dichotomy, popular and seemingly coherent though it is, is far more complex and means something quite different than authors or readers realize. It is usually taken to be a richer, more poetic, more mythologized version of the dichotomy between rationalism and intuitivism; that was how I meant it, and that usage was wrong for the reasons described above. The more serious error is that Apollonianism and Dionysianism, although intended to describe the differences between left-brained and right-brained mentalities, do nothing of the sort. Instead they describe a whole-brained mentality's wistful, romanticized fantasy of what those two modes might be like; the truth of the two half-wit, crack-brained mentalities is far darker and more dysfunctional than the Apollonian and Dionysian fantasies allow. All three mentalities, the whole-brained and both half-brained imbalances, exist in both Logos and Mythos cultures, but in different ratios. A Mythos culture will have whatever proportion of these three mentalities in its population that naturally developed there, but a Logos culture will tend to elevate left-brained mentalities to domination over the right-brained, with the whole-brained mentalities marginalized. None of this corresponds to a simple Apollonian-Dionysian dichotomy, even if that dichotomy had any validity outside the realm of poetry. Explaining Logos and Mythos culture using these terms was quite unhelpful.

Stripping these three false analogies back out of my explanation, we are still left with the original pair in the dichotomy underlying this first principle: Mythos culture and Logos culture. Aside from the confusion introduced by trying to explain them in terms of three supposedly analogous dichotomies, the most important problem is that in doing so I danced around the heart of the matter. Rather than draw further analogies to other dichotomies I will do better to explain Mythos and Logos cultures in terms of what they have in common; they are cultures first of all, so explaining them should begin with the nature and function of culture before contrasting their divergent expressions of it. I hope my next post will explain this crucial first principle underlying ancient Greek philosophy far more clearly.

Yours truly,

Rick

Postscript: And I hope I get my explanation of the second principle right the first time.

Thursday, August 31, 2006

Principle 1: Cultural Transition from Mythos to Logos

Dear Reader,

You are in luck. The first principle is the easiest, because you find its title confusing. That means you will question your assumptions about it. The others will be harder because you will be tempted by the titles to believe you already know what they mean, and you will be wrong about that.

We would identify ourselves as a logos culture. A logos culture distances itself from the immediacy of life, trusting rather to theories, principles, mathematics, and overt, conscious, analyzed information than to the naive, immediate, felt experience of being immersed in the details of life. That is, a logos culture trusts the conscious mind over the unconscious, trusts logic over feelings, intellect over intuition, the mind over the heart. Taken to extremes, nothing is to be respected as inherently authoritative; everything is required to justify itself; only things that pass our tests of the intellect are permitted to be considered true or valuable. That is, a logos culture trusts only reason, nothing else. Outside of the framework of rationality and the meaning we assign to things, we believe the cosmos is ultimately inherently meaningless, and hence, for our use and disposal as we see fit.

Although logos cultures pride ourselves on our objectivity and reason, like all cultures we have our irrational, subjective sides; we just do not identify ourselves with our irrational sides, pretend that side of us is not part of ourselves. This results in a certain ahistoricality, since the contempt of logos cultures for non-logos cultures is so intense that we cannot bear to identify ourselves with them in any way. Logos cultures insist on treating non-logos cultures as primitive versions of ourselves, unenlightened, pre-renaissance, lacking the preeminent value of all values to a logos culture - objective reason. We organize these two kinds of culture into a nominalist history of rational progress with ourselves - what a coincidence - as the advanced form. This polarization leads to an inability by logos cultures to explain our own origins, since we magnify the distance between ourselves and non-logos cultures to create a safe, impenetrable chasm, to assure ourselves there's nothing irrational left in us. In our mania for purging ourselves of the irrational, logos cultures create the ideal breeding grounds for two sets of delusions: 1) to overlook our own irrationalisms, since we hold them in such contempt, and 2) to overlook the wisdom of non-logos cultures, since we hold them too in such contempt.

The result is that the great blind spot of logos cultures is ourselves - our own origins, our unconscious natures, our wholes, and therefore the essence of what we really are. By the time logos cultures become logos cultures, we have lost the ability to explain honestly to ourselves where we came from, and as we will see, non-logos cultures cannot speak the language of logos cultures and so are equally unable to enlighten logos cultures as to our origins or ultimate nature.

But how do non-logos cultures see themselves? Do they imagine they are primitive, irrational, dangerous versions of us? Our culture prefers not to examine this question closely, to at most propose that non-logos cultures are so caught up in irrational systems of superstition that they cannot see the world clearly, let alone themselves or us. The idea that there might be an alternative form of logic about which cultures can be organized is threatening to our totalitarianizing culture, so we look away, distance ourselves as is our logos-cultural reflex with all things too intrinsically meaningful to submit to the rule of objective reason.

The alternative to logos cultures are mythos cultures, which dominate the history of the human species until recently. Mythos cultures are saturated with values, principles, feelings, stories, intuition, the unconscious, the soul, the mysterious, the divine. Where logos culture sees an objective, meaningless world to be ruled by the awesome power of human reason, mythos culture sees human reason at the mercy of a vast, powerful world ruled by powers beyond our comprehension and saturated with meaning. As Hans Jonas argues in The Phenomenon of Life, until recently the idea that the cosmos is largely lifeless and that life is extremely unusual - the commonsense belief of our logos culture - would be inconceivable in a mythos culture. Imagine a world without roads, parking lots, cities, dust bowls, massive garbage dumps, strip malls, strip mines, clear cuts, and so on; think about those stories of salmon runs so thick you could walk across their backs, herds of bison that stretched from horizon to horizon, flocks of birds so vast they covered the skies; imagine life pressing in on you from all sides - that is what the world used to be like. In such a world, life is the norm - lifelessness the exception - and for the longest time in human history the obvious conclusion is that there were no exceptions, that everything is alive, everything is conscious, everything is divine. As the early Greek philosopher Thales of Miletus wrote, All things are full of gods.

Mythos culture is a form of paleopsychology, synthesizing millennia of painfully accumulated folk wisdom and aiming to explain the opportunities and liabilities of human mind and culture in terms every member of that culture can understand, in stories. Every god in the Greek pantheon is a power that has authority over people - lust, greed, death, war, wisdom, envy, love, and so on - and the intersection of gods and men in those stories describe the relationships among those powers in our lives. As Moderns, we read the stories as either light entertainment or as opportunities to poke fun at what we perceive to be weaknesses in their explanation of the material world we have mapped so carefully, but we skim past the morals and object lessons. As a classic example, we think Oedipus is about some freak who slept with his mother, when instead it is the definitive treatment of how hubris can take even the most apparently blessed of people and transform him inexorably into the most cursed. We think the Iliad is the story of brave Achilles, or wily Odysseus, or powerful Agamemnon, when it is truly the story of doomed Hector who knows he is going to lose everything he ever loved and must nevertheless lead his people into the most glorious loss possible to teach the future about virtue because that is all that is left to salvage; and also it is about the squandering of an entire generation of the best and brightest Greeks and Trojans left dead on the plains of Troy over what was ultimately a domestic dispute. There are grim and vital lessons for humanity in the mythos culture of the archaic Greeks, not by coincidence but by design - this is what mythos culture is better at than logos culture.

In a logos culture, we teach history sliced into discrete facts and assemble them to achieve some kind of power over the world by predicting the future based on the past; logos culture prides itself on inventing history. In mythos culture, they taught history in terms of stories, geneologies, cosmologies - wholes impregnated with life lessons to create a population of people with shared values. Logos culture drives toward a system of laws, not men; mythos culture a system of men, not laws. So it is with every other field of study. Logos culture uses systems of dissection - analysis - to divide the cosmos's web of logic into abstract formulas each of which describes a tiny fragment of the cosmos which can then be controlled according to that formula, driving toward a view of the cosmos as an elaborate machine composed of manipulable parts. Mythos culture uses systems of composition - synthesis - to assemble the fragments of our understanding of the cosmos into a web of meaningful stories that describes that culture's lessons about Man's place in the cosmos. Logos culture uses abstraction, distance to acquire power; mythos culture uses intuition, immediacy to share meaning. The drive of logos culture is to put Nature in harmony with Man under Man's authority; the drive of mythos culture is to put Man in harmony with Nature under Nature's authority.

Where logos culture trusts the conscious mind, mythos culture trusts the unconscious. Where logos culture emphasizes the abstract and universal, mythos culture emphasizes the concrete and particular. Where logos culture is left-brained, mythos culture is right-brained. Where logos culture is Apollonian, mythos culture is Dionysian (no, not in the drunken, party animal sense, but in the embrace of the rest of ourselves beyond the rational mind, the embrace of mystery). Mythos culture is weak on analysis, on questioning assumptions, on disrupting moribund cultural structures, but logos culture is weak on synthesis, on promoting shared beliefs and values, on preserving and strengthening healthy cultural structures. Mythos culture is a nest, logos culture a knife. Neither is sufficient in the long run, which brings us back to the ancient Greeks.

In ancient Greek mythology are all the seeds of ancient Greek philosophy, and when the Greeks began writing theirs was thoroughly a mythos culture. The Greeks began their transformation as a collection of tribes with a common language and military culture of excellence but with diverse religious and political practices. A series of crises and opportunities drove the Greeks to unite as a people, forcing them to analyze their separate religious and tribal practices and deliberately, consciously weld them together into a single, shared culture, essentially crafting their new religion and laws by hand to accomplish this. Although they largely succeeded, the effort so transformed them as a people that they were driven into that explosive cultural revolution that transforms a mythos culture into a logos culture, but unlike almost any other culture in the history of the world, they wrote their way through the whole thing, essentially documenting the stages of thought and culture along the way from one side to the other, leaving us with all the evidence we need to understand the strengths and weaknesses of both types of culture.

Early in this transformation, their mythos culture began taking on logos characteristics as they began philosophizing about their culture, resulting in a remarkably self-aware mythos culture. Later, as they shifted into a logos culture they brought the mythos culture's emphasis on principles and values into their notions of objectivity and reason, resulting in a remarkably principled logos culture. In the end, they passed so far into logos culture that a nihilistic movement known as the sophists arose, arguing that nothing mattered but manipulating others to advance one's own self-interest. Greek culture dissolved into such a nihilism that later-stage Greek culture began to resemble our own, at which point Greek civilization collapsed into a series of devastating civil wars ended by conquest first by Macedonia and later by the Roman empire. The ancient Greeks rocketed through this entire arc of transformation in high gear, passing from mythos culture to logos culture to complete collapse in just a few centuries, analyzing themselves and documenting what they saw as they went.

There are three reasons why this principle of reading the ancient Greek philosophers in terms of their transition from mythos to logos culture is so crucial:

First, each ancient Greek philosopher wrote at some specific point along this arc of transformation, and many of them influenced the course of their culture's development by what they wrote. To understand any given philosopher of the ancient Greeks, we must understand when they wrote, what they would have so taken for granted as not to bother saying explicitly, what within that culture they were criticizing and why, and how and why their successors reacted to them as they did. Without understanding these things about each ancient Greek philosopher, we are guaranteed to misunderstand their intent. For example, although later logos philosophers are often as literal as we might be writing today and often focusing on dividing the cosmos up into analytical pieces, earlier mythos philosophers are often writing metaphorically, allusively, focusing on relating the cosmic forces with one another in order to understand the overall pattern. Where later philosophers are alarmed by their culture's decay into sophistry and arguing against nihilism, earlier philosophers are often criticizing mythographers for being overly rigid and credulous about their articles of faith.

We cannot understand Xenophanes unless we understand how early he came in this cycle, so we know he is writing so much about the gods because his culture is so steeped in religion that he has to grapple with that subject in detail if he is to move his culture ahead on any subject; from this perspective, we begin to appreciate his efforts to create the concept of philosophical inquiry, as well as his insistence on treating the cosmos as an integrated organism rather than just a space or a collection of things. We cannot grasp Thales when he writes everything is water unless we know he was the first to argue that there is a common material basis for all things (which is true and will later develop into Democritus's atomism), and that furthermore all things that appear stable actually flow (which is also true and will later develop into Heraclitus's dialectical materialism). His insights were revolutionary and necessary for everything that came later, but a modern, literalistic reading (how stupid - not everything is H2O! - what nonsense) misreads both his intent and his significance. So it is with each of the great Greek philosophers.

Second, beyond this principle's necessity for us to begin to comprehend any of these philosophers, we need to understand it in order to know what kind of perspective is being assumed relative to our own logos culture, whether we are looking at a mirror or criticism of our own type of culture, or of the mythos type, and to consider what that means for our own culture accordingly. This is a powerful source of insight if we use it correctly.

Third, this principle is the core explanation for why some of these thinkers were able to anticipate what we think of as purely modern thinking by over two thousand years. Without the benefit of modern technology, Democritus reasoned out the atomic basis of all matter. The scientists of the European renaissance all openly acknowledged their complete indebtedness to the Greek thinkers before them. The Greeks formalized the principles of democracy likewise. The invention of the alphabet, hyper-realistic art, the invention of philosophy along with the definition of all major subjects and boldest statements of all the alternative positions on each of those subjects - no matter where we look, we find the Greeks ahead of us in breadth and depth of innovation; we depend upon and build upon their much earlier work in the same areas. They could not have done these things had they remained a mythos culture - they would have lacked the systematic rigor and emphasis on an objective posture - but neither could they had they been merely a logos culture as we are - they would have lacked the rich foundation of values and principles, cultural assumptions that drove them to an excellence they took for granted, assumed as their debt to their divine ancestors, achievements of personal excellence and accomplishment that they needed as their only shot at immortality because of their beliefs about the afterlife. The ways in which their mythos culture enriched and even made possible their logos culture should teach us something fatally important about the limitations of logos culture alone, about our form of culture.

Philosophy was only made possible for them when the logos-impulse to shape themselves rationally as a people intersected with millennia of accumulated mythos-folk wisdom about the meaning of Man and Nature and the Divine. When their logos-rocket kicked in, their slow mythos liftoff had already done half the work for it, including build the rocket. The Greeks offer us a hint of what is possible if our systems of inquiry are grounded not in value neutrality but in complete dedication to principles and to the cultivation of greatness rather than mere satisfaction of appetites or pursuit of personal power, that is, to a marriage of both kinds of culture.

Yours truly,

Rick

Tuesday, August 29, 2006

Principles of Ancient Greek Philosophy

Dear Reader,

Just as good writing requires the author to understand and write to his audience, so good reading requires the reader to understand and read from the author. Though the first requirement is rarely followed, the second is rarely even acknowledged. To comprehend the Greek philosophical authors of twenty-five hundred years ago, who stretched their language and culture dramatically in the quest for unprecedented insights, such discipline on the part of readers is crucial.

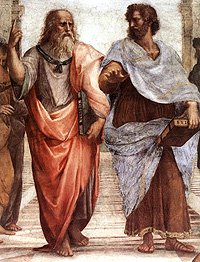

Understanding Heraclitus or any other ancient Greek philosopher is a challenge. Neither just like us nor primitive versions of us, the ancient Greeks conceived of the world very differently than we do. Where the range of our ideas is preformed by millennia of thinkers and writers formatting the world for us before we even begin to think for ourselves, the ancient Greek philosophers were fresher, more original, having to invent new ways of seeing the world from scratch. The Greeks were diverse and experimental, so writers from different places and times in the Greek world brought surprisingly different perspectives and assumptions to bear on their philosophizing. It is difficult to conceive of a philosopher as different from Heraclitus of Ephesus as is Parmenides, his contemporary from Elea. Nevertheless, the ancient Greeks interpreted the world not just from the viewpoint of their local customs and cultures but also through the unifying field of a common culture evidently created quite deliberately by the Greek tribes to help unite them into one people.

The unifying cultural principles underlying ancient Greek philosophy are the necessary context for interpreting those ancient writers, not only in the case of philosophers like Heraclitus of whom we have lost all but fragments but also of writers like Plato and Aristotle for whom we are lucky enough to have extensive collections of their books. When we do not understanding these principles, our cultural blinders drive us to misinterpret almost anything these philosophers wrote, to understand their words as we might have meant them had we written them rather than as their authors did, but once we begin to comprehend the principles, we find them everywhere referred to in various ways and begin to smell their implicit presence even where they are not referred to explicitly. These principles permeate their thought and writing.

Over the next seven blog posts, I will introduce and explore each of the seven principles.

Yours truly,

Rick

Sunday, August 27, 2006

Rashid and Surya are Growing

Dear Reader,

Dear Reader,Although you cannot see it in this picture, Rashid is larger than Surya, though both are still small kitties. Rashid's coat is glossy but a little coarse. He is a hands-on kind of boy, wanting to rub himself along everything, toys, legs, bedposts, your face, from the tip of his nose to the end of his tail, and he likes to hug things and bat them with his paws. He likes to give kisses, and will stretch or reach or climb up to your face to do it.

Surya is long and slender and has soft, soft fur. She has become very fast and tenacious, racing after toys and hanging onto them far more fiercely than Rashid. She is more impatient than Rashid with being held, wriggling after only a few seconds, except every once in a while when she lolls in my arms and purrs and purrs. When she freaks out, her thin tail puffs up to become unbelievably huge. She finds everything fascinating.

This is the week we're going to let them and Morgana start working out their issues together.

Yours truly,

Rick

Postscript: We took a host of photos this morning, but our babies do not like to sit still, and we had to chuck almost all of the photos because of blurring or empty frames.

Saturday, August 26, 2006

The Queen of Eene

Dear Reader,

The ongoing challenge in our household is to introduce our new kittens Rashid and Surya to our seventeen-year-old cat Morgana, aka The Queen of Eene. Morgana is very verbal, having much to say about things, and very particular as is typical of tortoiseshell cats; she's a tortie's tortie, and she wants things the way she wants them. She would rather not eat at all for days on end if the food, its presentation, its timing, and everything else about it isn't right, and as with food so with most other things. She's a gentle cat, surprisingly tolerant of children, very affectionate on her own terms, loving the rhythms of her day spiced with occasional novel curiosities. She used to be an unbelievable jumper, but settled down over the years. She still hates noises and loves fires and sunshine.

We got Rashid and Surya particularly for her, since after Shakti's death she has wandered about the house crying and looking for her. Unfortunately, so far she is very uncomfortable with the kittens, and they with her. Most likely, we will need to just let them work it out with however much hissing and posturing it takes for them to figure out their new relationship.

Yours truly,

Rick

Something New to Think With

Dear Reader,

Albert Einstein is supposed to have said or written "The significant problems we face cannot be solved at the same level of thinking we were at when we created them." Or perhaps it was "The problems that exist in the world today cannot be solved by the level of thinking that created them." Maybe "Problems cannot be solved at the same level of awareness that created them." Or is it "We can't solve problems by using the same kind of thinking we used when we created them?" Could it be "No problem can be solved from the same consciousness that created it?" Perhaps he wrote or said none of these things. Perhaps all of them.

These are popular quotes to attribute to Einstein, but most people attributing any of these things to him do not seem to care whether or not they are really his words. They are putting words in his mouth to strengthen what they want to say with an appeal to authority, which I wrote about in an earlier blog entry. If we are fortunate, the words they are putting in his mouth are indeed his own. They do not know, and neither do I.

Whoever wrote or said these words, I believe them. Or more correctly, any mode of thinking permits an individual or a culture to solve certain problems and requires them to create others, and those it creates it cannot solve because they tend to accumulate around its blind spots and Achilles' heels. These occur as the necessary flip sides of its strengths, and so cannot be removed without also removing those strengths and indeed the very character of that mode of thinking. That is, the distinctive strengths of any system simultaneously and necessarily generate equally distinctive weaknesses that can only be avoided by radically transforming that system at its roots, changing the very strengths that gave it its character and identity. To break free of those genetic defects, the only option is metamorphosis, which unfortunately is anathema to hubristic ego, so the defects stay.

We create most of our own problems, and not by accident but by the very forms of our character, by our mentalities, that is, our forms of reasoning and motivation. This is why technology will never solve our primary problems. New science and new technology are something new to think about, but we think about them with the same minds that created the problems in the first place. Science does not lead to enlightenment; the Nazis loved science so much that to advance certain scientific programs after World War II America had to import Nazi scientists. Science is proudly value-neutral, focused on utility, a tool at home in the hands of sinners and saints alike. Tools operate upon extrinsics. Our core problems are intrinsic, where tools cannot reach.

Somehow, mysteriously to us, every new promise of utopia ends up just another market commodity. We focus on changing the externals that were never truly responsible for our predicaments, then wonder that the problems persist or even accelerate under the new conditions, like bacteria growing ever more virulent under the pressure of our wonder drugs. Alfred Nobel, inventor of dynamite was appalled when his fabulous new tool for construction was promptly put to work blowing up his fellow human beings, and created the Nobel Prizes as an apology to humanity, or so the story goes.

In other words, the problems we face are primarily ad hominem. There is nothing so noble that a barbarian will not put it to barbaric purposes, and in the great scheme of things we are all barbarians. The problem is not the tools at our disposal, not the things we have to think about. The problem is what we are thinking with. If the human race is to survive, we need something new to think with. The current model is dangerously defective. And no, the answer is not artificial intelligence, nanotechnology, or genetic engineering; those answers represent more of the same level of thinking that got us into this mess.

My friend Kenneth Smith likes to say "Every other field of study gives you something new to think about. Only philosophy gives you something new to think with." This philosophy is not the empty academic cataloging of philosophical writers and their dates and titles and quotations, nor is it the abstracted, schizophrenic elaboration of complex but arbitrary schemes of ideal forms and their interrelationships beloved by timid intellectuals. Rather, what gives us something new to think with is the lifelong project of cultivating a better character in the Ancient Greek sense, of striving to develop eudaimonea,a coherent inner cosmos, of struggling against ourself to find our blind spots and feel out the architecture of our character so we can figure out how to grow beyond what we are today - to deliberately undertake our own maturation.

In a culture like ours, none of us has eudaimonea. We all have dysdaimonea - dysfunctional characters that afflict us so that we in turn afflict the world. In the immortal words of Walter Crawford Kelly, Jr., creator of the classic comic Pogo, "We have met the enemy and he is us." If we want to make a better world, we must first make better people. The kind of world we have is what the kind of people we are can and must create. Above all, the problem is not all those other people - it is ourselves. We must make ourselves better from the inside out. Doing this will change how we see the world, how we value it, and how we think about it, and that will change what we do about it.

Yours truly,

Rick

Monday, August 21, 2006

Verbal Medicine

Dear Reader,

When I was younger, I believed we were all created equal, that anyone could do what anyone else could do. I well understood some of the depths to which we could sink, having read extensively about the Holocaust, but I believed education and communication could save the human race. I idolized and idealized science.

Step by step, I was compelled out of these illusions. I came to understand that most people work very hard not to hear or learn anything that requires them to transform, that they resent anyone who tries to reach out to them through their walls. I learned that science is what it is, not what it could be, and the two are worlds apart.

So, step by step I learned to say less and less of what I truly believed outside my circle of friends. Ironically, in some quarters of my life this too was unacceptable: I could neither say the things I believed without incurring arguments that seemed never to progress to understanding, nor was I to be permitted to withdraw from those pointless, soul-killing conversations. My faith in communication has bounced off the bottom many times in the last few years.

I learned, though, that it is too late in my life for me to stop trying to communicate. It has become a need. Verbal Medicine may be a pun, but for me it is also serious business. Even if no one listens or understands or responds, I cannot be healthy unless I strive to put my thoughts and feelings into words, unless I try to reach out not just to those I know and love but also to others I do not yet know but who may find in my words a kindred spirit.

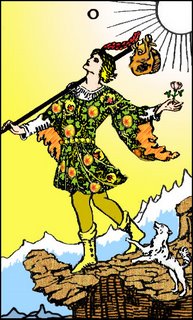

It is a bit ridiculous to do this, to cast my words out and entertain even a faint idea that they may find their intended audience. I am put in mind of that first tarot card: The Fool, stepping off the cliff, as we are all fools who try to make anything happen in this world, never even remotely comprehending what we will set in motion nor how crazy it is to imagine the cosmic forces that invisibly crowd our lives will ever permit our arrow to hit the mark we intend for it. Yet without that ridiculous hope and effort we would be no more than jetsam.

We attract more flies with honey than vinegar. I could be much more entertaining in this blog than I am. I do know how. I have written for decades now, and have run Dungeons and Dragons games since 1978. I could spin the fun stories, be witty, work harder to be the entertainer, but I do not want flies. I want to reach out neither to the walking appetites who make up the vast ballast of our culture, nor to the walking calculators who run it. I hope my writing style and topics are as unentertaining for such people as possible. I hope that somehow the fewest of the few, the adults out there, the ones who bring their heart and head into everything they do, the ones with the endless curiosity, the paradoxically playful and serious ones, the ones who care more about truth and justice and art and hope and other people and other species than they do about feeling good or acquiring status or power . . . crazy as it may be, I hope that something in my vinegar writing draws such people.

Because the verbal medicine I really need is not just self-expression, which I worshipped as an end in itself as a teenager and which now I find fairly futile, but dialog with other nuts like me. I know you are out there. We are not alone. We are just atomized, segregated from each other by the lack of the kinds of social contexts that would nurture us as a permanent community. Perhaps we could consider some kind of mutual activity together other than merely satisfying our appetites or indulging in temporary pretend-escape from this mess we all find ourselves in. Maybe we could heal ourselves with a little help from each other. Maybe we could heal more than that, if we worked together. Who knows?

Like I said: crazy; The Fool. But there it is. I gotta try.

Yours truly,

Rick

Thursday, August 17, 2006

Gender in English, Ancient and Modern

Dear Reader,

Many writers have remarked on the problem of expressing or not expressing gender in Modern English. Women ask why man is the generic form, as in mankind, and why woman is derivative, as though lesser. I have heard people attempting to justify this on religious grounds, since Eve was created from Adam's rib, and is therefore derivative.

Efforts to correct the perceived male bias in the language has resulted in fireman being replaced with fire fighter, mailman being replaced by mail carrier, and so on. Although these efforts to repair our lopsided language are now a fait accompli, and occasionally strengthen the term so changed, they all miss the point. The use of man as the male form of human is a corruption of the original definition in Old English, which was balanced with respect to gender. The reason we sometimes use Man in a generic sense, as in "Man is a tool user" is because Old English Mann meant human only in the generic, gender-independent sense of a person. A male human is a mann, and a female human is a mann.

Woman is a corrupted form of wifmann, or wife-person. As Kathleen Herbert writes in Peace Weavers and Shield Maidens: Women in Early English Society, the origin of wif is a bit of a mystery, but the best guess is that it is related to wefan, to weave. Old English writing is full of references to the primary role of wife-people as Peace Weavers. This weaving role of wife-people was not restricted to physical weaving. A study of Old English social rites and rituals, legends and stories, makes the original gender role of wife-people very clear as the bearers of culture and the weavers of civilization. The whole purpose of the striving of the males, the wars, the hunting, the building, was to create a safe haven within which wife-people would create civilization. Their role originally was not to be a mere helpmeet; that is a foreign gender role introduced into Old English culture later.

The lost word in Modern English is the specific term for a male person. In Old English that was waepmann, a weapon-person. The Old English world was very dangerous, and every weapon-person carried a spear starting in boyhood. The role of a weapon-person was to place his body and weapons between wife-people and danger, to protect the hall, the village, the gardens, and the fields where the wife-people worked to create the civilization that made life worth living. The weapon-person was a living contradiction, on the one hand striving for individual prowess and excellence at any cost, on the other needing to submerge his ego for the good of society, to bond together with other weapon-people to create a reliable shield wall. Weapon-people bound themselves together by personal oaths and vows not to abstract, corruptible organizations, but to each other and to their future actions, and the cornerstone of that Old English culture was the witnessing of those oaths and vows and how they were carried out. It was not the original role of weapon-people to rule the world and dominate the wife-people; that is a foreign gender role introduced into Old English culture later.

There was a pun in the name weapon-person, one noted by Shakespeare and others, as to whether the male's weapon referred to his instrument of war or his instrument of sex, captured in the modern word tool. This pun was seriously meant, because the other role of the male was to beget children, but this latter meaning was more directly captured by a second word for a male person: wermann. This prefix is related to the modern were as in werewolf. It meant male specifically in the sense of a person capable of getting a woman with child, which after all is pretty much the core definition of male. Were also meant a husband, the companion of a wife, so a newlywed couple were pronounced were and wife, that is, man and woman.

Obviously, the noun forms are not the only ones lacking balance in Modern English. The adjectives (male and female) and pronouns (he and she) both lack the general form as an option, though English is clearly evolving toward having they become the general pronoun, and the adjectives also perpetuate the false sense of the male term as the original and the female as the derivative (curiously, the two terms male and female come from two different languages and were originally unrelated and spelled unalike).

Language permits thought in human beings, and limitations or deformations of language limit or deform thought. It is a typically Modern thing to do to let the limits and deformations of our gender terminology spread throughout the language rather than repair them even at the foundations of the language.

These ancient gender terms were not the denatured, abstracted, empty designations of sex to the Old English that man and woman are to Moderns. They carried powerful cultural meanings that went to the heart of how ancient English society was structured and why. The loss of so many unreplaced terms, and the erosion of meaning from those we have kept, has left holes in our ability to comprehend ourselves and our respective roles in the world. As those roles shifted over time, the meanings of the words could have shifted with them, but instead most such meaning has been stripped from them, leaving them empty abstractions. The many new terms borrowed from other languages or invented wholesale have not filled those gaps, but rather have expanded our language and ideas in new directions, changing the overall shape of our minds and culture, altering what we can or cannot express or even conceive of. We imagine that the changes must be improvements only because it flatters us to believe it. Rather than striving to skip past these changes with quick judgments of whether they constitute progress, we ought to look at their pattern and ask ourselves what they mean. As individual personalities and as a culture, over the last two thousand years how have we been changing? What are we becoming?

Unless we honestly examine that question, we cannot know ourselves.

Yours truly,

Rick

Wednesday, August 16, 2006

Don't Fear the River

Dear Reader,

Dear Reader,Prior to Serge Mouraviev's current project, there have only been a handful of serious efforts to collect together much of the Heraclitea. In general, scholars have been too busy advocating their interpretations of Heraclitus to be bothered with evaluating the whole field of prior interpretations. Likewise, few authors have bothered to review and evaluate even just the variant sources for the surviving fragments, to assess the discrepencies and try to understand what the original text may have been. Most translators have simply selected a trusted or favored collection, such as the Diels-Kranz collection, and assumed that their chosen collection adequately separates genuine Heraclitus fragments from spurious ones.

This is a dangerous assumption. With so few surviving fragments, many of which are so profound as to cast all of Heraclitus's philosophy in a different light, omitting even one genuine fragment can cause the translator or interpreter to misread everything.

I happen to have an example with which you may be familiar. Both Plutarch and Plato write that Heraclitus said you cannot step twice into the same river. This must be the best known Heraclitus quote, and for many of us it represents one of perhaps a half-dozen truly crucial keys to understanding his philosophy. If you accept this as a geniune Heraclitean quote, it changes everything about how you read Heraclitus.

For that reason, numerous scholars have labored to discredit it. If Heraclitus is a philosopher of universal flux, then he stands in opposition to Parmenides and Plato, who argued that only unchanging ideal forms are real and that all flux is illusory. To many, Plato is a sacred ox who must not be gored. Heraclitus's philosophy is too potent to ignore, so for Platonists Heraclitus must either be discredited or coopted.

For years the standard approach was to discredit him by arguing that he did indeed advocate universal flux, and that the idea of universal flux leads to such logical inconsistencies that his entire philosophy collapses in upon itself. The problem with this approach was that it is patently untrue, and philosophers and scholars free of the sway of neo-Platonism continued to explore the coherency of his philosophy.

In recent times, therefore, Heraclitus's opponents have changed tactics and tried to coopt him by a variety of devices, all of which hinge on demonstrating that universal flux is a misreading of Heraclitus, that perhaps after all he was a safe proto-Platonist. All such attempts have to deal with that river quote, along with its two friends. Here are all three along with their sources (I am using Charles H. Kahn's translations from The Art and Thought of Heraclitus: An edition of the fragments with translation and commentary here, and can recommend his book to others readily, though Philip Wheelwright's Heraclitus is my favorite interpretation):

First: As they step into the same rivers, other and still other waters flow upon them. This is quoted by Arius Didymus, and also by Cleanthes, and most scholars accept it as a legitimate fragment of Heraclitus's writing.

Second: According to Heraclitus one cannot step twice into the same river, nor can one grasp any mortal substance in a stable condition, but by the intensity and the rapidity of change it scatters and again gathers. Or rather, not again nor later but at the same time it forms and dissolves, and approaches and departs. This statement is from Plutarch and contains the most familiar form of the fragment, that one cannot step twice into the same river. Although this is a paraphrase, it must be very close to Heraclitus's original form, because another paraphrase of the same idea, this one by Plato, uses the same wording: Heraclitus says, doesn't he, that all things move on and nothing stands still, and comparing things to the stream of a river he said that you cannot step twice into the same river. Charles Kahn's analysis of these two independent yet converging paraphrases is compelling, i.e., that none of the attempts that have been made to make them go away carries anything like the strength of the evidence itself, that the convergence of these two separate but reliable sources almost certainly means Heraclitus wrote something very much like this.

The attempts by Kirk, Marcovich, Reinhardt, and others to argue that this most famous fragment of Heraclitus is merely a misquotation say less about the evidence than they do about the intentions of those making the attempt. Their arguments amount to little more than the a priori decision that Heraclitus would only have made one statement that mentioned a river, so they can reduce the discussion to arguing over which is the most authentic or the most clearly a literal quote. Since the second statement is a paraphrase, if a close one, they discard it in favor of the first one. Of course, why there can only have been one statement about a river is passed over by these interpreters, since that assumption cannot bear scrutiny, and once one questions that the next question that comes to mind is why these commentators are so eager to get rid of two of the river statements. Given the profound, two thousand five hundred year history of hostility between the philosophers of change and the philosophers of permanence, it cannot be a coincidence that the form favored by these scholars is the one most compatible with a philosophy of permanence. Scholars like to pretend to objectivity, and for this reason they especially need their motivations scrutinized closely to understand the real import of their arguments.

Other scholars, not motivated by the age-old antagonism, may yet be misled by the fragmentary nature of Heraclitus's surviving text into believing the original was fragmentary as well, but we do have a couple of compound fragments. In those compound fragments we have from Heraclitus, we can see that he loved to juxtapose similar statements that clarified one another, especially if the second amplified or developed the paradoxes of the first, and these two statements fit that pattern very well. Kahn rightly argues that these first two statements most likely occurred together, one after the other, in Heraclitus's original text.

Before Plato, Cratylus amplified this second statement of Heraclitus's about the river with his own argument that you cannot even step in the river once, since you are changing even as you make the attempt. Although Kahn reads this as Cratylus seeking to one-up Heraclitus, I believe it was meant more as explanation, since it is an inescapable conclusion of Heraclitus's philosophy of dynamic flux if you fully come to grips with it. With Cratylus's statement in mind, consider this third statement about the river attributed to Heraclitus:

Third: Into the same rivers we step and do not step, we are and we are not. This is quoted by a much later writer named Heraclitus Homericus, who wrote a commentary on Homer; that is, the later commentator Heraclitus Homericus is quoting the earlier philosopher Heraclitus, if we accept this as a genuine fragment. The later Roman writer Seneca also quotes this line as the philosopher Heraclitus's. Scholars tend to agree that Seneca and Heraclitus Homericus were quoting a common source, but disagree about whether that source was the philosopher Heraclitus or perhaps some later writer, possibly a skeptic. For example, despite Kahn's position that those discounting the second statement are defying the evidence, three seems to exceed Kahn's own limit, for he argues that this third form is not authentic, despite reasonable sources. His argument: he "can only see it as a thinly disguised paraphrase" of other fragments. That's it. No careful evaluation, no additional evidence not available to the reader, just a strong feeling based on its resemblance. Ironically, this is the same reasoning in Kirk, Marcovich, and Reinhardt that he earlier dismissed, rightly, as flawed.

How can Kahn fall prey to the same reasoning himself that he so clearly identifies and refutes in others, and on the same subject? Even a casual reading of Kahn reveals he lacks the motivation of the others to miscast Heraclitus as agreeing with Parmenides and Plato about the unchanging nature of the true cosmos; after all, he is quite careful about showing the many ways Heraclitus exhorts us to see flux as the true nature of the cosmos. We cannot really know, but a reasonable guess would be that most common of human failings that afflicts us all, fools and wise men alike: hubris, in this case the temptation to mold the material with unwarranted confidence, to feel that even without access to the original text he nevertheless knows its character so well that he can feel his way to the truth. Unfortunately, if this is the case, and he gives us no reason to doubt it, then he like so many others has forgotten that we all know things that are not true, and so we should beware such confidence.

All we have of Heraclitus are fragments attested by later writers. We must tread very cautiously, ruling out possibilities with the humble recognition that we have not one original scrap of his book with which to make a definitive statement. We must resort to that proper default position of the natural philosopher in the face of the cosmos, humility, the acceptance of the limitations of our own reason, and consequently the need to become comfortable with uncertainty. If the only defensible criteria we have for choosing legitimate fragments are 1) the reliability of the sources, and 2) the consistency with the style and content of other fragments accepted as legitimate, then we have to accept this third fragment, however tentatively as legitimate, no matter how we may feel about it or how clever an argument we may construct about it. Kahn's failure to define his criteria and stick to them, left him making judgments based on how they, in his own words, "seem to me," which is ironically precisely the translation of the Greek expression doke moi, origin of the term doxa, which the Greek philosophers including Heraclitus defined as the uninformed, unphilosophical, unreliable opinions of the masses; they held doxa in the utmost contempt, which is why they became philosophers.

As a development of the previous two statements, this third one shifts the emphasis from the flux of things to the paradoxical nature of things in flux, a necessary development of the explanation, especially to Heraclitus whose writing thrives on paradoxes. He implicitly argues repeatedly throughout his writings that the mathematician's aversion to paradoxes is perverse in a cosmos that teems with natural paradoxes. Indeed, he argues that the cosmos can only be understood through layers of paradox, both in the contradictory forces that bring about the phenomena we perceive, and in the paradoxical resulting nature of things. After all, if you are continuously changing, as science would agree, then you both are the same person from one moment to the next and also are not exactly the same person. Likewise the river into which you step changes and becomes different, even as it remains identifiably the same. Identity, according to Heraclitus, is a paradox, and this third statement is completely in keeping with his emphasis on paradox, making it a fitting conclusion to the argument developed by the first two statements, whether or not they originally appeared in that order.

All of which is to say I agree with Kahn in accepting the validity of the second statement, and I disagree with him by accepting, however tentatively, the third as well. I see no good reason to doubt that Heraclitus wrote all three statements and placed them closely together to illustrate the nature of our relationship to the cosmos when both it and we as part of it are in endless flux. Although he has a reputation for being obscure, in the few compound fragments we have and in the other potential ones we might try to reconstruct by rearranging closely related fragments Heraclitus does appear to make some effort to explain his ideas through metaphor and development rather than restricting himself to the most pithy, paradoxical possible formulations of these concepts.

After all, later in the same dialogue in which Plato paraphrases Heraclitus's second statement, he adds another paraphrase: panta rhei, that is, all things flow. This is the most succinct form of this thread of Heraclitus's teachings, and all three river statements, as well as Cratylus's extension, are inevitable implications of this two-word explosive nugget of wisdom. Had Heraclitus been the obscurantist he is reputed to be, he would have left it at that, but instead in the image of the river he worked out a reasonable metaphor for explaining the flow of change. These three river statements by Heraclitus are therefore not problems to be avoided but opportunities to more fully comprehend the profound and vital nuance of his philosophy.

Returning to the subject of hubris, if you conduct a few careful web searches for variations on the famous "You cannot step twice into the same river" statement, you will find truckloads of authors declaring with great confidence that smart people know Heraclitus never actually wrote this. They ape the empty reasoning of Marcovich and others on this subject without actually working out even so little on their own, yet present their "conclusion" with authority. Here again, as in so many other ways, humans display their love of appearing wise without working for wisdom, of pretending to authority they do not possess, of attracting followers they can not lead, of simultaneously casting themselves as unusually observant and independent-minded when they are instead typically blind and prone to follow the lead of others unquestioningly. As Heraclitus argued, most people do not know why they want the things they want, nor why they believe the things they believe, and you certainly cannot trust them to tell you those things accurately. Even the most seemingly objective and rational person builds his arguments as mere rationalizations of his prejudices and urges.

Critics of the World Wide Web decry its lack of quality control, but the information you can observe about human nature on the web is worth all the misinformation about lesser topics. Here are all these people laboring to miscast Heraclitus as not fundamentally in conflict with Parmenides and Plato, and most of them clearly do not even realize what the larger conflict is about or what the implications might be of their position. Truly, most of what people do with their brains should not be called thinking, and most of what is written does not qualify as communication. This is part of makes Heraclitus and his work so remarkable, and also part of what makes Serge Mouraviev's Heraclitea project so welcome and necessary.

Yours truly,

Rick

Tuesday, August 08, 2006

Rashid and Surya

Dear Reader,

The picture is of Rashid sleeping on Surya the night we brought them home. He's all black except for pale nipples when he rolls onto his back and stretches, and he tends to express affection as fiercely as he plays, butting his face into yours and purring passionately. She's a tabby with tortoiseshell coloring, as you can see in the stripes on her leg; she's more likely to curl up and purr in your lap, and in play she's more careful in her stalking but more determined in hanging onto her kills. Although they are not brother and sister by blood, as you can see they act like it. They have only two speeds, and here you can see them in their lower gear, when they purr and purr. Neither has yet mastered the meow, although Rashid occasionally mews, but Rashid has been making hilarious efforts to growl and hiss during play; Surya is remarkably silent when not purring, though she is the more ardent purrer.

The collar tag you can see is a thing of the past; she stripped him out of his in the second week--what a great toy!--and we had to remove hers last week because it was too tight and the end had been cut too short to loosen it successfully. Fortunately they are strictly indoor cats; more than that, until tomorrow they are strictly guest-bedroom cats. We introduce them to the rest of the house, at least the parts we are opening up to them, tomorrow.

Yours truly,

Rick

Wednesday, July 12, 2006

Kitty Day

Dear Reader,

Dear Reader,July 12th in the Phinney Creek household will hereafter be known as Kitty Day, when in Shakti's memory we brought home a pair of kittens for Morgana. We are busily engaged in preparations, and hope to have the kittens home by 2:00 this afternoon. We are adopting them from the Progressive Animal Welfare Society (PAWS), at their Cat City location at 85th and Greenwood. I go now to gather toys and other supplies.

Yours truly,

Rick

Tuesday, June 06, 2006

The Gifts of Grief and Fear

Dear Reader,

Dear Reader,When I was young, I wanted to be like Mr. Spock from Star Trek, free from emotion and able to think rationally at all times. At least, that is how I interpreted the character when I was young.

Later, I came to understand that he was not free of emotion, as the alien Vulcan race on that show is described, because only his father was Vulcan; his mother was human. He was trying to be a pure Vulcan, but he was not. He had feelings, which he did not want, so he repressed them, and several episodes and movies hinged on the difference.

I followed suit in part, and struggled to supppress feelings I believed were negative, such as fear, anger, and grief. I succeeded to a surprising degree, but in doing so I incurred the liability of all those who separate their intellect from their feelings. Seeking to become free of certain emotions, I instead made them invisible to me, lost that sixth sense most people have that allows them to use their feelings like antennae to help them think, lost the ability to keep my feelings in true balance by integrating them into my personality (since I was unaware of them) and instead became controlled by them. They had free rein down in the dark places of my unconscious. For decades, it was as though I had lost a sense other people have, a kind of blindness, and also could not at times predict or explain my own behavior.

When I began counseling in April of 1987, my counselor noticed these blind spots in my emotions and struggled for years to get me to even realize they were there. For almost nineteen years despite discussing sometimes harrowing things I never cried in therapy. About halfway through that time I finally came to agree with my counselor about the consequences of my emotional blindness, and particularly came to agree that my cycles of depression were directly related to it, that escaping from those debillitating crashes was in part going to require regaining the use of those feelings. After much work we finally began to push through and find the anger, but we never did get to the grief and fear in any depth . . .

. . . until my kitty Shakti fell seriously ill in January, rapidly weakened, and died February 21st.

Her illness and death changed everything for me. It was very much like the experience of someone blind since childhood regaining sight. I cried more during that month and even since than in the last thirty years combined. I can feel sorrow and grief in response to movies and songs, in parting from friends and relatives, in thinking back on other friends and relatives who have died--in short, I am beginning to feel appropriate shades of grief now at all those times when an emotionally healthy person would.

And during my recent vacation on the Navajo reservation, I discovered fears I had never known while hiking on steep cliffs, not crippling fears, but good, healthy responses to risky situations. I am starting to feel the nuances of concern and fear that characterize emotional health.